Prioritize by Bang for the Buck

The most challenging problems in software engineering have little to do with software engineering. They're the same problems that every industry faces: what should we do? how do we work together? how do we balance quality with velocity? These questions seldom have the definitive answers that engineers crave but that doesn't prevent us from approximating some quantitative analysis.

For instance, take prioritizing a roadmap of projects. I've seen an entire room full of otherwise exceptional people come up completely stumped trying to decide whether a project is worth doing.

It's therefore unsurprising that there are so many methodologies purporting to be the Holy Grail of project prioritization. Each method has its advocates and each advocate has their opinions and — because each roadmap is executed only once and can't really be A/B tested — it's quite a challenge to determine quantitatively which one works best.

Challenge accepted.

Prioritization Methods

Here are some popular methods for roadmap planning. Each one has its champions so we're going to toss them into our arena to fight it out.

Emergent. The project roadmap is a FIFO queue. New projects are added to the roadmap as they're conceived and executed when it's their up next. Most people using this method might not describe it that way but if you're not prioritizing based on any sort of criteria (or deferring to a HiPPO), then sorting is essentially random.

Value-Based. Projects are prioritized based on the size of their opportunity. An time-honored method and known by many names over the years: move the needle, focus on the bottom line, do stuff that matters, Highest Value First (HVF). This method might also be considered a proxy for "squeaky wheel syndrome"; if there's a project that would make so much money that people keep bringing it up.

Shortest Job First (SJF). Projects are prioritized by how quickly they can be completed. Basically the same as "pick the low-hanging fruit" (itself a bad metaphor) but productivity professionals had to give it an acronym. There are psychological benefits to this approach beyond the financial, not to mention the concept of Net Present Value (NPV) suggests that having something now is often better than having something later.

Bang for the Buck. Projects are prioritized based on both their value and the effort. This method is also known as Cost of Delay Divided by Duration (CD3) or Weighted Shortest Job First (WSJF) to those acronym-addicted productivity professionals. Keep your eye on this one.

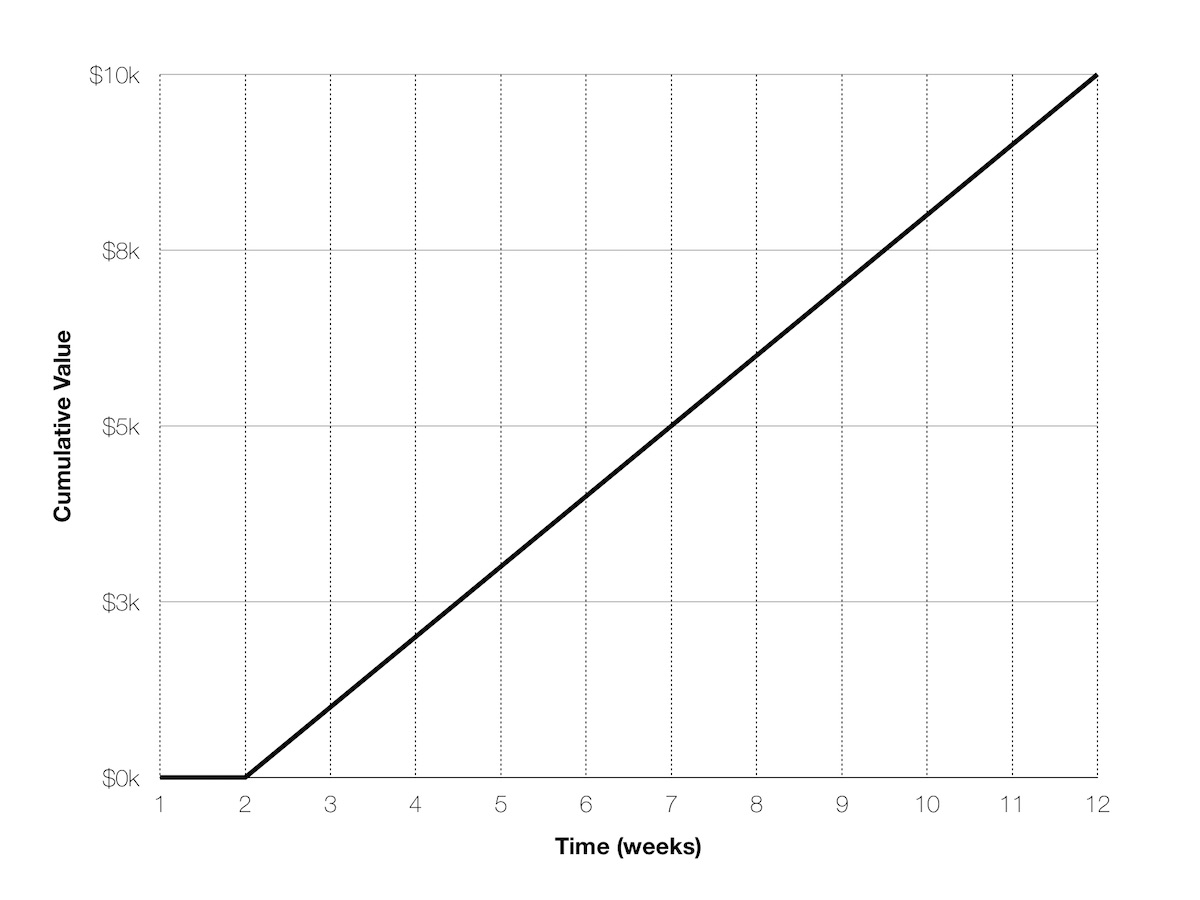

How can we compare these different methods? I've put together a model based on cumulative value. If a project — once delivered — makes $1k a week and takes 2 weeks to deliver, the cumulative value of that project would look like this:

About what we'd expect. No revenue for the first two weeks and $1k each week after that, with a cumulative total of $10k (10 weeks at $1k) by the end of the quarter.

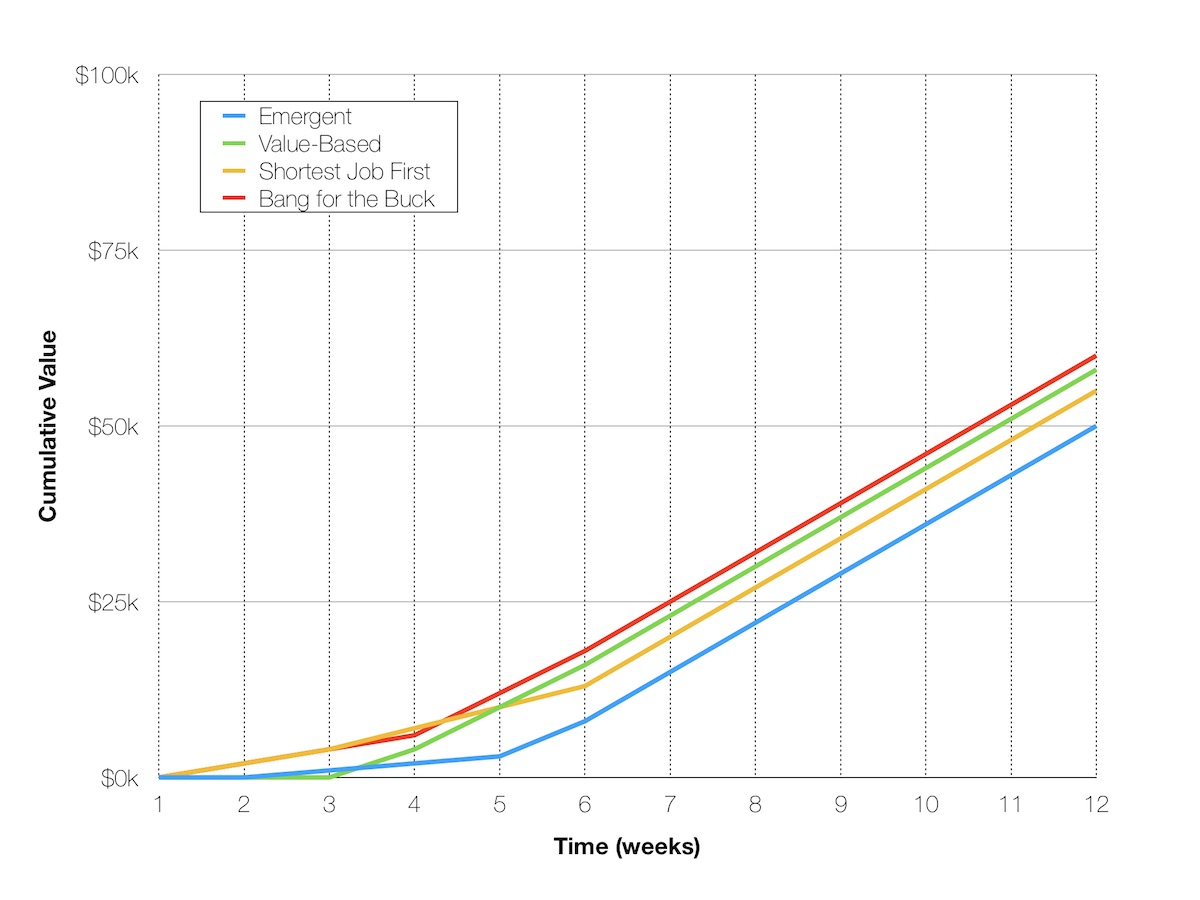

We can apply a cumulative value approach to an entire roadmap. Let's say we have three projects: A, B, and C.

- Project A would make $1k per week and take two weeks to deliver.

- Project B would make $4k per week and take three weeks to deliver.

- Project C would make $2k per week and take one week to deliver.

Each prioritization method would stage these projects differently. Emergent would tackle them [A, B, C], Value-Based [B, C, A], Shortest Job First [C, A, B] and Bang for the Buck [C, B, A].

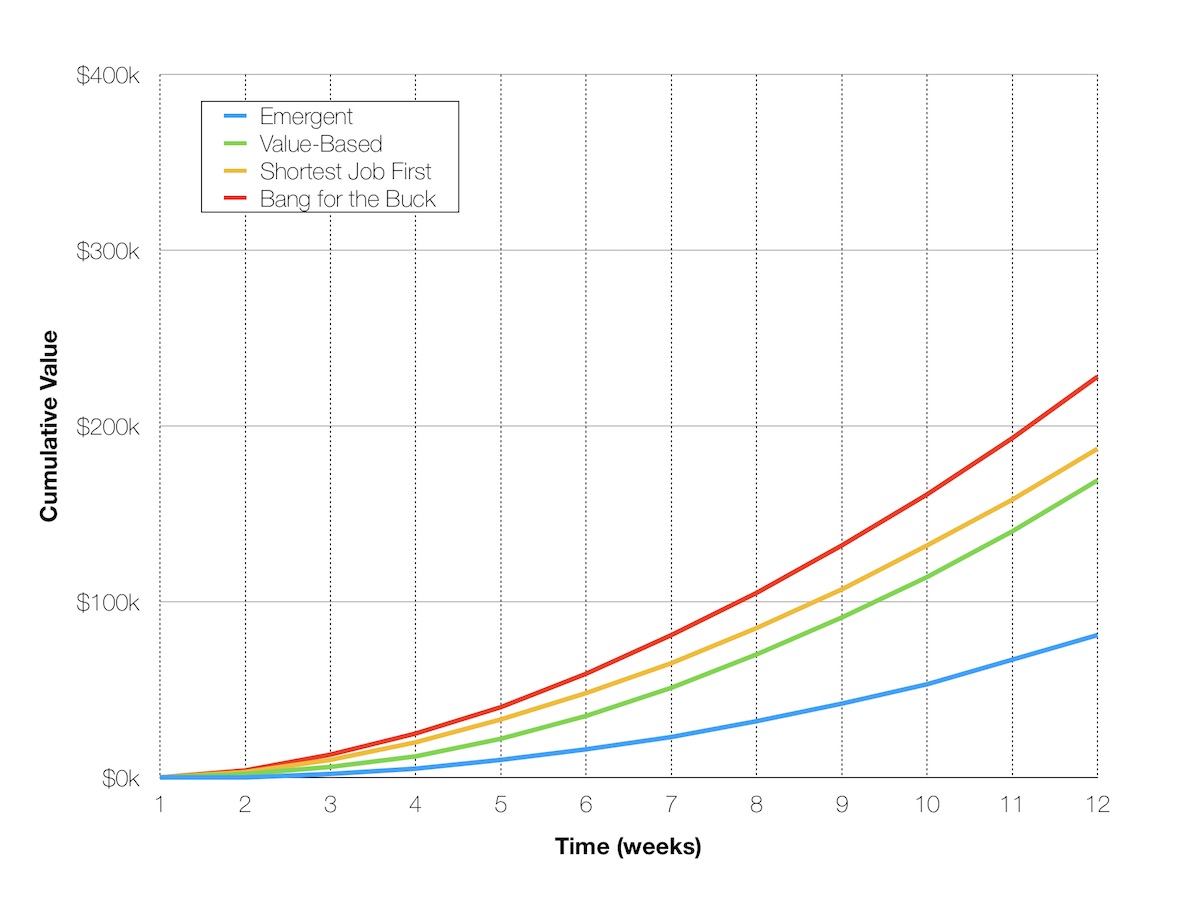

So what do the cumulative values for each approach look like?

Hey look, Bang for the Buck wins! This result might not surprise you based on the title of this post, but let's throw some more "real world" examples at it.

Prioritizing a Roadmap

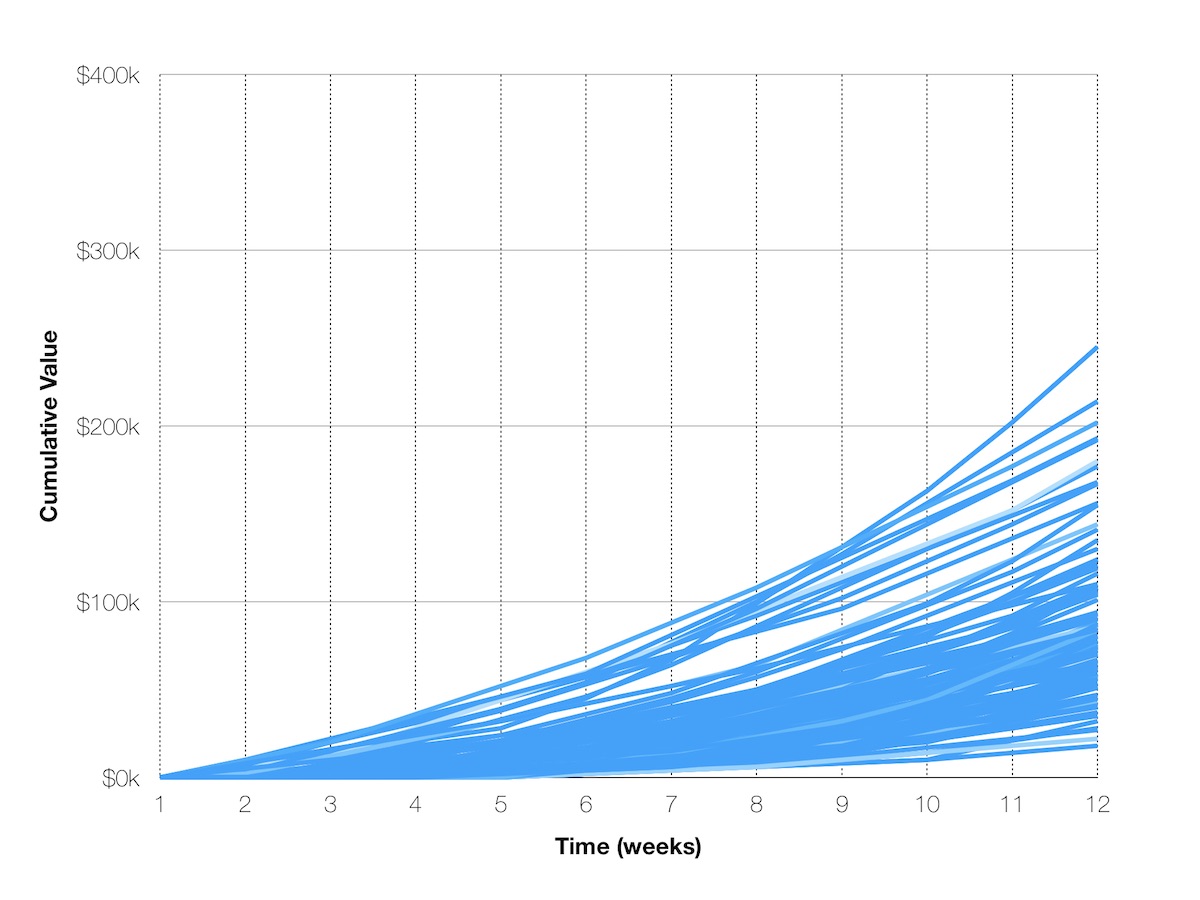

It seems reasonable to me that an organization could easily generate a list of 40 projects that they could attempt at any given time. These projects would all yield different values to the organization — which I assume would be distributed by a power curve and not a normal curve. There are only a few really great ideas and a lot more meh to bad ideas.

Let's generate a random roadmap of 40 projects, give each project a value and a duration, and then prioritize that roadmap using the Emergent method. In fact, let's do that 100 times and see what we get.

As expected, a random sorting algorithm generates some pretty random looking data. But even here there's a clear pattern. While going with your gut occasionally yields a fantastic ($333k!) cumulative value, the average over these 100 runs is only about $86k.

Bad Estimations

Quantitative prioritization methods are often rejected for being too "Crystal Ball" compared with qualitiative methods like MoSCoW. It's a lot easier to tell if something is urgent or not urgent than how long it might take. Indeed, software projects are notoriously late (the Standish Group estimates 53% of them are late or over budget) so we need to build the fact that humans are bad at estimating duration into our model.

Why stop there? Humans are also pretty bad at estimating value. How many times have you worked on a project that was going to change everything only to find that it barely made a dent?

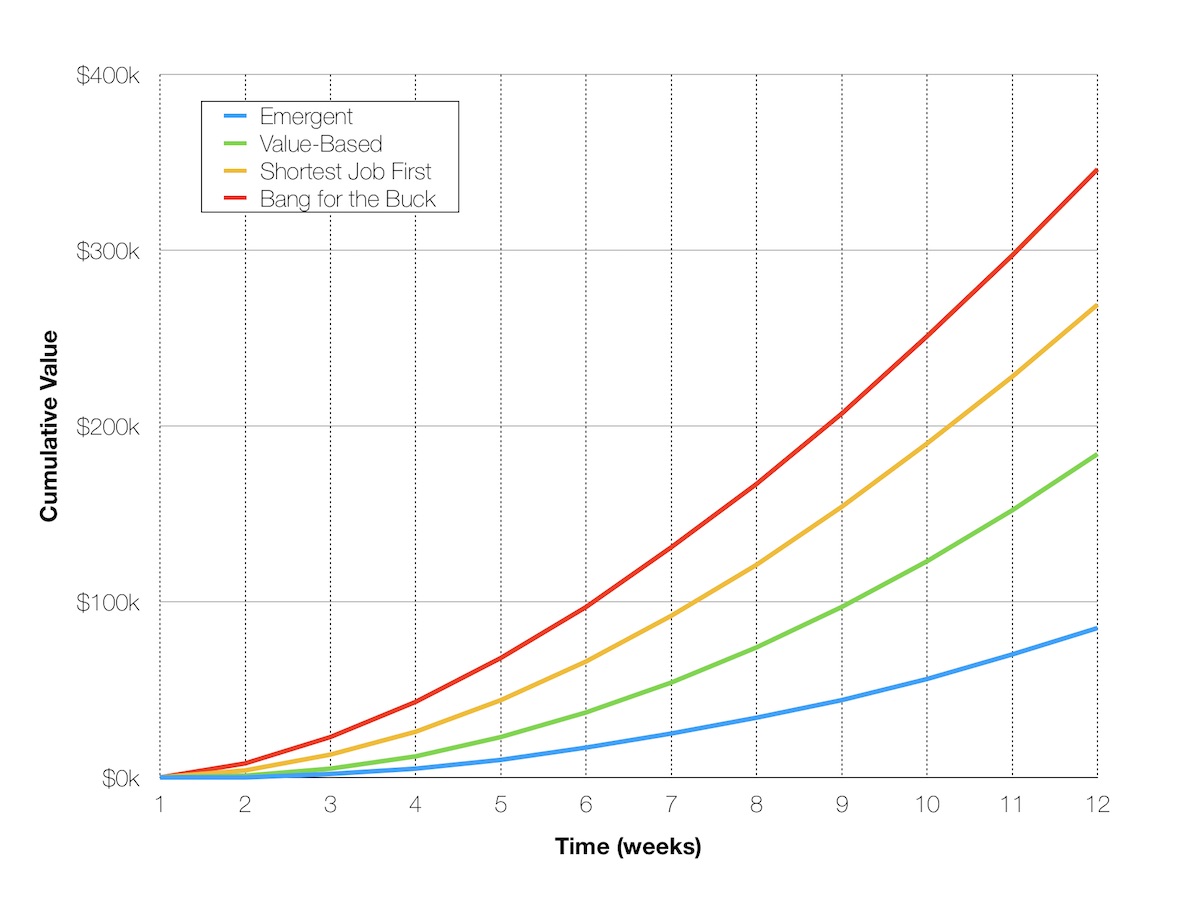

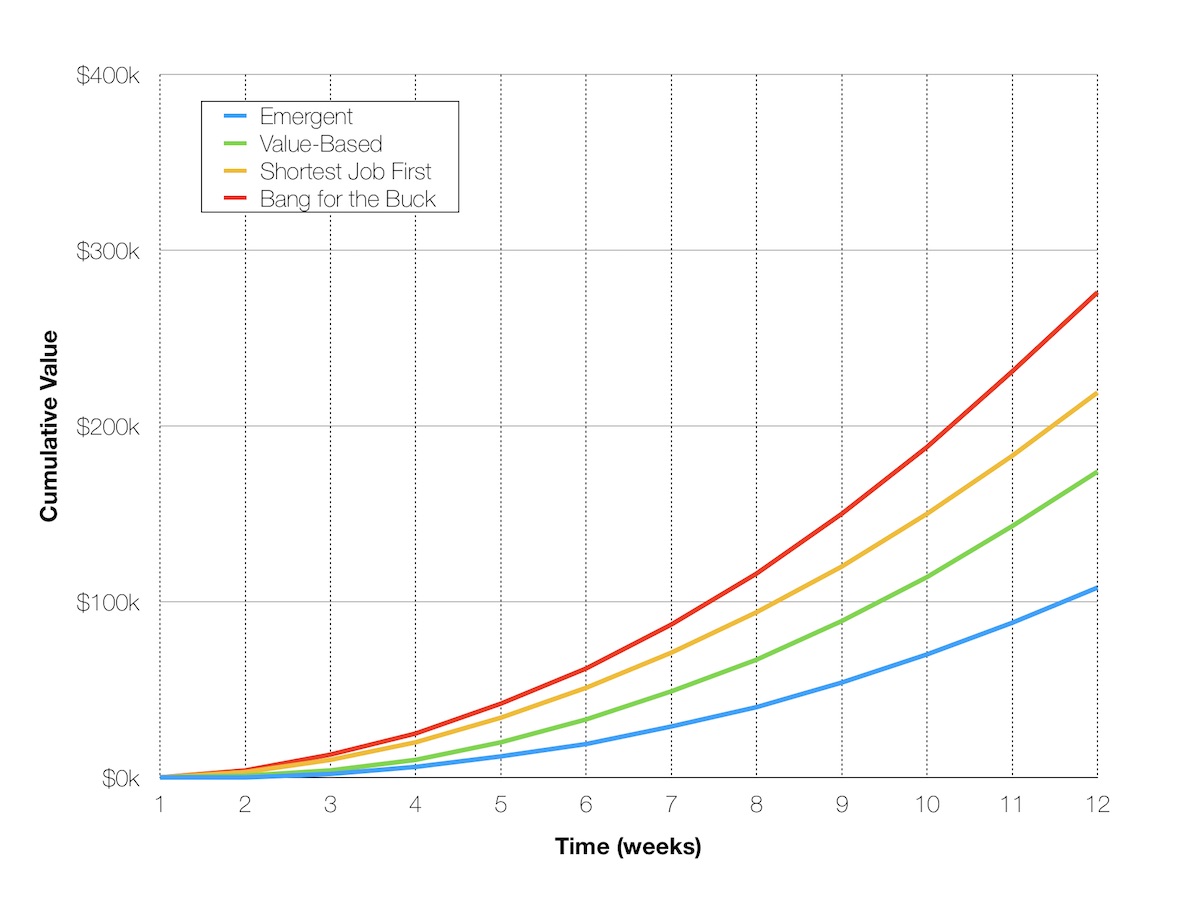

Here's the average cumulative value over 1000 runs for each of our prioritization methods given perfect knowledge:

And here they are again when the prioritization is based on badly estimated values and durations instead of actual:

A lot worse, right? The important thing to note here is that, even when our estimates are awful, it doesn't change the relative performance of our methods. A cloudy Crystal Ball is still better than ignoring value or duration when prioritizing.

So far, all of these analyses assume that your organization operates with discrete "projects" and not the more agile "pipelines" that are becoming increasingly popular (and even the Standish Group suggests are more successful). Let's take a look at one more chart. In this one, prioritization is still based on imperfect knowledge but, whenever a project is completed, the remaining roadmap is re-estimated and re-prioritized based on those new estimates.

The result is 22% better than not re-estimating and 80% as good as perfect knowledge!

Takeaways

Prioritizing by any quantitative method (i.e. not just someone's opinion) outperforms the Emergent method, regardless of whether you're operating with perfect or imperfect knowledge.

Prioritizing by Bang for the Buck outperforms all other methods, again regardless of perfect or imperfect knowledge. This result actually surprised me, because I expected the bad estimates for both value and duration to compound since it considers both of them.

When operating with imperfect knowledge, re-estimating and re-prioritizing results in average cumulative values that are almost as good as those for perfect knowledge.

One takeaway that my model does not show, because I could only show so many things at a time, is that limiting project size greatly improves overall cumulative value. Splitting a large project into an MVP, 1.0, 2.0, etc. means value starts accumulating earlier and, if necessary, the remaining scope can be de-prioritized versus other projects.

I hope folks find this useful. I originally presented it to other engineering managers at Chartboost and a few of them suggested I write it up into a blog post. The second half of the presentation was about deriving semi-accurate numbers for value and duration — since Bang for the Buck (or CD3) highly depends on them — and using them to sort an existing roadmap. We've actually done this a few quarters now and it's astonishing to see it play out. Dark horse projects reveal their worth while pet projects go down in flames. If you're interesting in seeing that part, ping me.